THERE are many reasons why I shouldn’t be here. If you’d shown my 10-year-old self my life as it is now, he’d have been stunned, mostly because he half-expected an early death.

My father, who had Marfan Syndrome, the genetic condition I have, died when he was in his mid-40s.

I was just two, and the conventional medical wisdom of the time was that this sort of life expectancy was normal.

Marfan is known as a “disorder of connective tissue”, meaning numerous systems of the body can be affected – the connective tissue of the heart, joints, eyes are liable to strain or tear.

In my teens, I had multiple spinal surgeries, but there was always the spectre of sudden aortic dissection: a potentially life-threatening tear in the aorta, the body’s largest blood vessel. Like walking around under a storm cloud, never knowing if or when the lightning would strike.

If you’d shown my 20-year-old self my life now, he’d have said, ‘Well, I’m not disabled, not really, I mean, I’m not disadvantaged by my body, there’d be other people who really are’.

At that age, I felt profoundly stigmatised, faltering under the weight of other people’s intrusive attention, a different kind of lightning, that kept striking.

My sense back then was that disability was about impairment. They use wheelchairs. They’re blind or deaf. They’re intellectually disabled. But not me. I just had a differently shaped body, which was other people’s problem, not mine.

As if I could keep those things discreet.

Back then, in the films, television dramas and books I consumed, there were disabled characters, invariably marginal or two-dimensionally pathetic or tragic.

Their existence was functional, a resource to be mined. Their bodies were metaphorically monumental, looming over the narrative, yet somehow hollow, without the fullness of agency.

I certainly didn’t know any disabled authors.

This is an edited extract of the Association for the Study of Australian Literature Patron’s Lecture, delivered at UniSA Creative’s Finding Australia’s Disabled Authors online symposium.

BECOMING A WRITER WITHIN A COMMUNITY

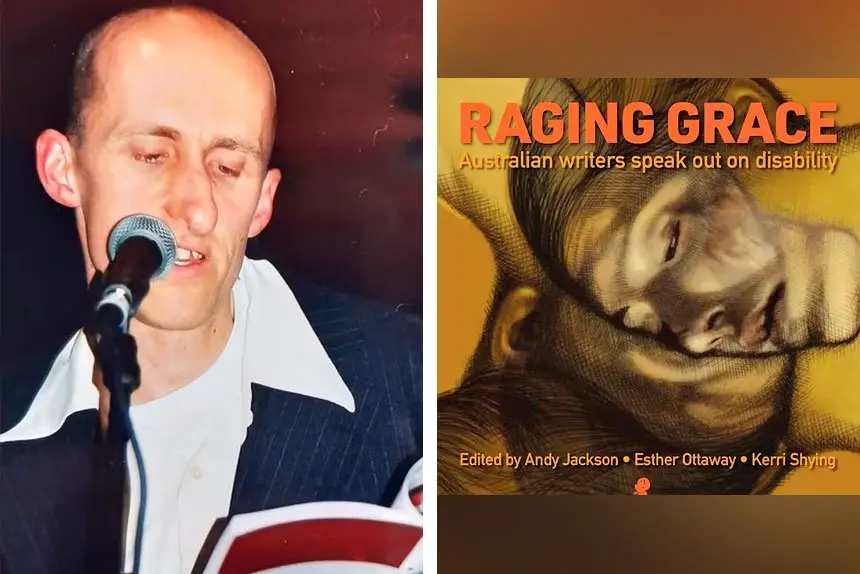

My 35-year-old self would mostly be surprised at the distance I’ve travelled as a writer. From open mic poetry nights in Fitzroy and Brunswick, via publication in photocopied zines and established literary journals, onto my first book of poems (then more), grants, residencies, a PhD in disability poetics, the Prime Minister’s Literary Award for Poetry – and now teaching creative writing at the University of Melbourne.

These, of course, are only the outward markers. What’s most potent for me is the sense that, in spite of my ongoing sense of dislocation and marginality, I do belong within a net of support and meaning-making.

I’m part of a community of poets and writers. A community of disabled people and people with disabilities, people who know chronic illness, the flux of mental health, who know what it’s like to be othered. I also live as a non-Indigenous person on Dja Dja Wurrung country, whose elders have cared for their land, kept culture alive, and resisted colonisation and its brutal extractions.

An awareness of where we are situated, a felt sense of relationship with others like and unlike us, a consciousness of the histories and political forces that shape us, a hunch that our woundedness is not separate from the woundedness of the entire biosphere: none of this just happens automatically, though it emerges from a very subtle inner resonance.

It has to be attended to, nurtured with curiosity and empathy, within a community. Because disability – as a socially-constructed reality, and as an identity that is claimed – is not essentially a category, but a centre of gravity every body is drawn towards.

This may not be the conception of disability you’re used to.

DISABILITY AS HUMAN EXPERIENCE

The social model of disability is the idea that what makes someone disabled are the social, political, medical, institutional, architectural and cultural forces and structures. Stairs (for people using wheelchairs) and stares (for those who look, or move, or talk in a non-normative way, where normal is a kind of platonic abstraction of what humans ought to be).

But disability is also a fundamental aspect of human experience, with its own magnetism or impersonal charisma. Disability is an unavoidable bedrock of being alive.

There is a tension here, of course. Between disability as a dimension of discrimination, which creates barriers we want to dismantle, and disability as an inherent aspect of an embodiment that is precarious, mortal and relational.

I am here because some of the barriers that impeded me have been, if not removed, then softened, weakened. Shame, stigma, an internalised sense of being less-than, abnormal, sub-normal: these things are being slowly eroded.

Not, fundamentally, through any great effort on my part, but through the accumulated efforts and energies of communities that have gone before me, and that exist around me.

HOW CAN WE BEST FLOURISH?

In late 2021, the Health Transformation Lab at RMIT University announced their Writing the Future of Health Fellowship. The successful writer would be paid for six months to work on a project of their choice. The call for applications emphasised innovation, creativity and collaboration. It invited a Melbourne writer to address the question: what does the future of health look like? I proposed a collaboration: an anthology of poems, essays and hybrid pieces by disabled writers. It has been published as Raging Grace: Australian Writers Speak Out on Disability.

RAGING GRACE: AUSTRALIAN WRITERS SPEAK OUT ON DISABILITY

When your body-mind is in upheaval, or is deemed troublesome, how do you find a way forward?

In the shadow of an ecological and social crisis, whose voices do we need to pay attention to?

The poems, essays and artworks in this groundbreaking anthology answer both these questions at the same time.

Written collaboratively and in conversation, they harness rage and grace to speak back to unhealthy, alienating systems and experiences.

Both prophetic and celebratory, Raging Grace affirms disability and neurodivergence as unique sources of truth telling, and collaboration as a radical model for collective health.

To purchase, look for the title online.

Source: Friday essay: ‘I know my ache is not your pain’ – disabled writers imagine a healthier world (theconversation.com)